Rendering techniques: the dance between server and client - Part 1

Feast your eyes on more dazzling designs like this from my colleague, the enchantress of illustrations, at

Bogi

Feast your eyes on more dazzling designs like this from my colleague, the enchantress of illustrations, at

Bogi

Sat Nov 18 2023

This blog post navigates the progression from static HTML pages to advanced interactive web apps, spotlighting essential technologies and their impact on the web dev. Ideal for enthusiasts keen to understand different rendering techniques and their applications.

When starting a new project and selecting the tech stack, the process can seem overwhelming. With a multitude of frameworks, technologies, various architectures, and rendering patterns to choose from, the decision isn't straightforward. In this exploration, I will delve into how initial state is managed across these diverse techniques and aim to clarify them by examining the evolution of web development.

By the end of this post series, I hope you'll be able to distinguish between the real techniques listed and the fake ones I've sprinkled in to keep things interesting. Let's go!

But wait here is a video on the blog post:

Let's rewind to the early stages of the internet's integration into daily life. During this era, Netscape reigned as the dominant browser, primarily interpreting HTML, which meant that most websites were static.

The dark ages

Soon, the demand for more dynamic web experiences grew. This led to the development of PHP, a scripting language designed for server-side execution. With PHP, web pages were dynamically rendered on the server, allowing the content and appearance of websites to change in response to different data inputs. This era marked the beginning of multi-page websites, offering more dynamic content than their static predecessors. However, despite these advancements, the level of user interactivity on these sites remained somewhat limited.

Here we have the initial three rendering techniques:

- Static rendering: This is the simplest form of rendering, where web pages are purely static, with content directly written in HTML. These pages don't change unless manually updated by the web developer.

- Server-Side Scripting (SSS) with php: This technique introduced dynamic content generation. PHP scripts, executed on the server, dynamically generate HTML content before sending it to the browser. This method allowed for more personalized and data-driven web pages.

- Multi-Page Application (MPA): In this approach, each route or link the user clicks loads an entirely new page from the server. This can be either a static HTML page or a dynamically generated page via server-side rendering (SSR). MPAs represent a more traditional web navigation model, where each click results in a full page refresh.

The Elightment

As web pages grew more complex and demanded greater interactivity, JavaScript (JS) was introduced, ushering in what some might call a 'delightful nightmare' in web development. This pivotal moment marked the beginning of an era filled with both excitement and challenges. With the adoption of ECMAScript 3 (ES3), JavaScript quickly evolved, bringing not only interactive elements to web pages but also introducing asynchronous functionality. This made browsers significantly more capable and versatile.

However, this rapid advancement coincided with the dot-com bubble burst in 1999. The economic downturn that followed resulted in a slowdown in technological progress. It took a whole decade for the next major standard, ECMAScript 5, to be established. In this period, the pace of web development innovation significantly decelerated, and the practices established by ES3 became the prevailing standard for a while, marking a phase of both maturity and a somewhat ironic pause in the otherwise fast-paced world of web development.

For the following decade, web development largely maintained the status quo established by the advancements in JavaScript. But let's pause here for a moment and, to dial down the suspense (or perhaps to set more realistic expectations), let's face an anticlimactic truth: this, in many ways, still represents the state of the web today.

Over the past 25 years, Content Management Systems (CMS) have predominantly ruled the web. While we're about to delve into various fancy and sophisticated techniques as highlighted in our initial discussion, it's important to recognize that it took a considerable amount of time before another industry standard emerged. Right now, we're in a phase where we're trying out new things in web development, and personally, I find this really exciting.

Before 2009, coinciding with another market crash, the prevalent web development approach primarily involved PHP and jQuery. This setup offered a decent User Experience (UX), largely due to its performance efficiency. The server managed the majority of processing tasks, while the browser provided just a hint of interactivity. However, this approach gradually began to challenge the Developer Experience (DX). For instance:

-

Error-Prone Process: The reliance on PHP for backend logic and jQuery for frontend scripting often led to complex interactions between the two layers, increasing the likelihood of bugs and errors. Developers frequently faced challenges in ensuring consistent behavior across different parts of the application.

-

Duplicate Logic for Validation: Validation routines often needed to be implemented in both PHP (server-side) and jQuery (client-side) to ensure data integrity and responsive user feedback. This duplication not only increased the workload but also raised the potential for inconsistencies, especially if updates were not mirrored across both platforms.

Scenario: You're updating a user registration form to include an optional phone number field, which users can add if they wish to provide their contact details.

- Server-Side Validation (PHP): On the PHP side, you need to write code to validate the phone number when the form is submitted. This includes checks for the correct format, length, and possibly even verifying that the number is not already in use (if uniqueness is a requirement).

if (!empty($_POST['phone'])) { if (!preg_match("/^[0-9]{10}$/", $_POST['phone'])) { // Handle validation error } else { // Process valid phone number } }- Client-Side Validation (jQuery): On the client side, using jQuery, you need to duplicate this validation logic to provide immediate feedback to the user without requiring a page reload. This involves writing a jQuery function that triggers when the phone field loses focus or when the form is about to be submitted.

$('#phone').on('blur', function () { var phone = $(this).val(); if (!phone.match(/^[0-9]{10}$/)) { // Show error message } else { // Hide error message } }); -

Slow Development: This architecture necessitated a lot of back-and-forth between server and client-side code, slowing down the development process. Making changes often required updates in multiple places, leading to increased development time and difficulty in maintenance.

SPA

The introduction of Single-Page Applications (SPA) marked a significant shift in web development, bringing notable improvements in both User Experience (UX) and Developer Experience (DX). Frameworks like Knockout and Angular played pivotal roles in this transformation.

-

User Experience (UX) Enhancements with SPAs:

- Seamless Interactions: Unlike traditional multi-page websites, SPAs allowed for fluid, app-like user experiences. Pages loaded faster, and users enjoyed seamless interactions without the constant reloading of pages.

- Responsive Feedback: SPAs provided immediate feedback to user interactions, making the web application feel more intuitive and dynamic.

-

Developer Experience (DX) Improvements:

- Knockout: Introduced around 2010, Knockout was one of the early frameworks to utilize the MVVM (Model-View-ViewModel) pattern. It allowed developers to create rich, responsive displays and editor user interfaces with a clean underlying data model. Its main feature, declarative bindings, simplified the synchronization between the HTML UI and JavaScript data models.

- Angular: Developed by Google, Angular brought a comprehensive solution to building SPAs. It offered a robust framework with features like two-way data binding, modular development, and dependency injection, greatly simplifying the development of complex applications. Angular also addressed many of the challenges associated with SPAs, such as SEO optimization and initial loading performance.

-

Overall Impact:

- Streamlined Development: With frameworks like Knockout and Angular, developers could build complex, interactive web applications more efficiently. The need for duplicating logic between the server and client was greatly reduced. Additionally, these frameworks simplified application bootstrapping and event handling. Developers no longer needed to worry about the intricacies of initializing applications or manually adding event listeners. This automation and reduction in boilerplate code, along with a declarative approach to UI definition and data binding, meant that the overall development process was not only more efficient but also less prone to errors. Maintenance and scalability were enhanced as well, due to the organized code structure and extensive community support provided by these frameworks.

- Easier Maintenance and Scalability: These frameworks provided a more organized structure for code, making it easier to maintain and scale applications. They also offered extensive community support and resources, further aiding development.

The adoption of the MEAN stack (MongoDB, Express.js, AngularJS, and Node.js) in web development signified a notable shift in how applications managed state, particularly with the transition of interactivity and rendering responsibilities predominantly to the client side. AngularJS facilitated a significant portion of the application's state management on the client side. This front-end framework handled both rendering and user interactions within the browser, reducing the server's involvement in these areas. The creation of dynamic user interfaces became more streamlined, as the framework provided a robust structure for managing the UI and its state, allowing for real-time updates and interactivity.

-

The UX improved:

- no refresh on page navigation

- highly interactive apps

-

The DX improved:

- unified mental model

- faster development that scales with complexity

- rendering and interactivity united into a single framework

As the landscape of web development continued to evolve, new frameworks and libraries emerged, further revolutionizing the field. React, in particular, gained prominence and quickly became the most popular framework, setting the stage for the birth of numerous other post-react-frameworks.

In essence, the growth of web applications led to the emergence of numerous specialized libraries to tackle repeating patterns, but this also introduced challenges in dependency management and application performance. The development landscape became a complex environment where careful consideration was needed to maintain a balance between functionality, performance, and user experience.

Instead of calling the server multiple times to gather the state and render what is needed? Why not go back to the server?

Before we start hot-potatoing the state between the client and server, let's take a step back and clearly define User Experience (UX) and Developer Experience (DX). We'll see how they relate to the state management and rendering techniques we've discussed so far.

UX

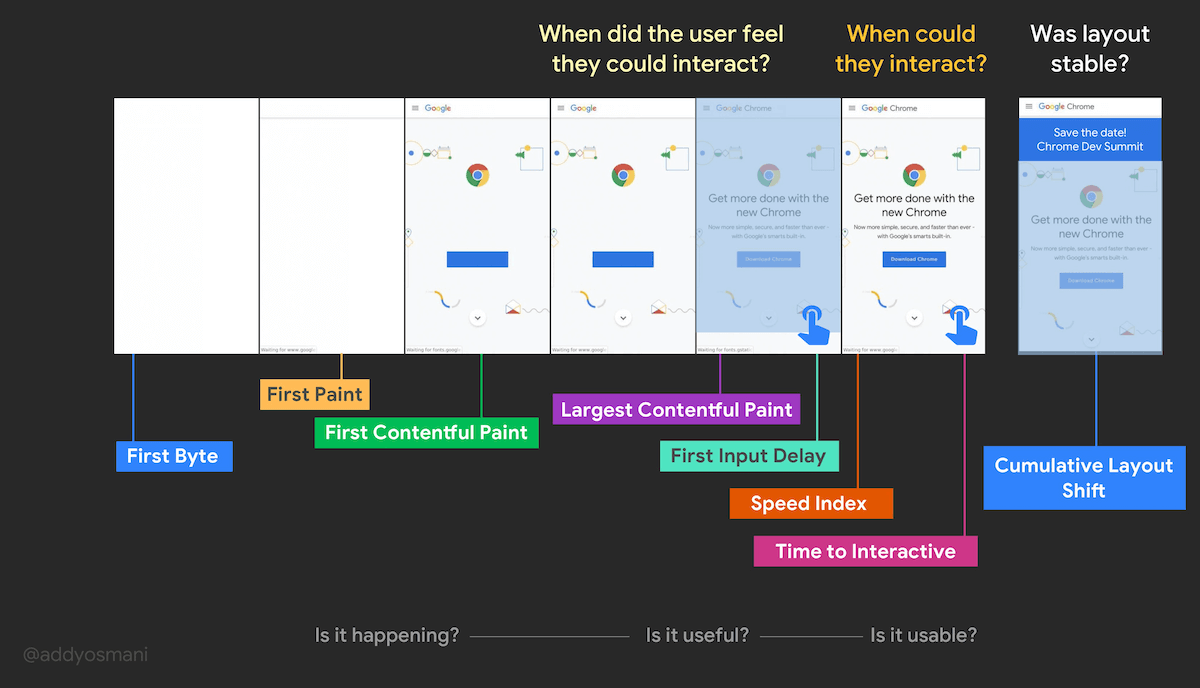

Core Web Vitals are a set of specific factors that Google considers important in a webpage's overall user experience.

- Time to First Byte (TTFB): This metric measures the time from the start of the initial navigation until the first byte of the page is received by the browser.

- First Contentful Paint (FCP): This metric measures the time from navigation to the time when the browser renders the first bit of content from the DOM.

- Largest Contentful Paint (LCP): This metric measures the time it takes for the largest content element in the viewport to become visible. It's an important indicator of perceived loading speed because it marks the point at which the main content of the page has likely loaded.

- Time to Interactive (TTI): This metric measures the time from navigation to when the page is capable of reliably responding to user input quickly.

- Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS): This metric measures the sum total of all individual layout shift scores for every unexpected layout shift that occurs during the entire lifespan of the page.

- First Input Delay (FID): This metric measures the time from when a user first interacts with a page (i.e., when they click a link, tap on a button, or use a custom, JavaScript-powered control) to the time when the browser is actually able to begin processing event handlers in response to that interaction.

BTW, I stole this concept from Advanced Rendering Patterns: Lydia Hallie, but I think it's a great way to understand the relationship between DX and UX.

DX

Then we have the Developer Experience (DX), which is a measure of how easy it is to develop and maintain a web application. It encompasses a wide range of factors, including:

- Build Times: The project should build fast for quick iteration and deployment

- Server Cost: The website should limit and optimize the server execution time to reduce execution costs

- Dynamic Content: The page should be able to load dynamic content performantly

- Rollbacks: A project's development can easily be reverted to a previous version

- Uptime: Users should always be able to visit your website though operational servers

- Infrastructure: Your project can easily grow or shrink without running into performance issues

This idea is from JavaScript Streaming: A Qwik Glimpse Into The Future - Shai Reznik which is another view on how DX and UX are related.

- Static Websites (Early 1990s):

- UX: Initially offering basic user experiences, static websites provided straightforward access to information with fast loading times and simple navigation.

- DX: Simple creation using HTML and CSS; however, managing a large number of static files became cumbersome as websites grew.

- Multi-Page Applications (MPA) (Mid to Late 1990s):

- UX: MPAs offered a traditional web experience with full page reloads, familiar to users but sometimes leading to slower interactions.

- DX: Straightforward building and maintenance, but managing state across pages and backend complexities increased with scale.

- Dynamic Websites (Late 1990s to Early 2000s):

- UX: Improved by allowing personalized content and interactive features, leading to more engaging web pages.

- DX: Introduction of server-side scripting increased complexity but enabled more powerful applications and functionalities.

- MPA + JavaScript for Reactivity (Early to Mid 2000s):

- UX: Enhanced by adding more dynamic and responsive elements within pages, improving interactivity without full page reloads.

- DX: Front-end complexity increased as developers managed both server-side and client-side code.

- Rich Internet Applications (RIA) (Mid 2000s):

- UX: Provided app-like experiences in the browser, significantly enhancing interactivity and visual appeal.

- DX: Development often involved specialized, proprietary frameworks like Adobe Flash, leading to a steep learning curve.

- Single-Page Applications (SPA) (Late 2000s to 2010s):

- UX: Revolutionized user experience with smooth, native-app-like transitions and real-time updates.

- DX: Required mastering modern JavaScript frameworks, a significant time and resource investment for developers.

- Hybrid SPA + Server-Side Rendering (SSR) (2010s to Present):

- UX: Combines the interactivity of SPAs with the performance and SEO benefits of server-side rendering, offering fast and engaging experiences.

- DX: Adds complexity in managing both server-side and client-side logic, challenging optimization and maintenance.

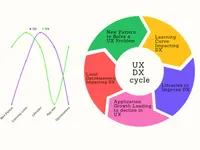

Through the history of web dev we've seen the dance between server and client, and how it has evolved to meet the needs of both users and developers. I think the cycle can be described as follows:

-

Invention of a New Pattern to Solve a UX Problem: Innovation often begins with the identification of a UX issue. A new design pattern, technique, or technology is developed to enhance the user's interaction with the software. This improvement is typically focused on making the application more intuitive, faster, or more enjoyable for the user.

-

Learning Curve Impacting DX: With the adoption of any new pattern or technology, there's a learning curve for developers. Initially, this can negatively impact DX, as developers need to invest time and effort to understand, implement, and master the new approach. During this phase, productivity might decrease, and there could be an increase in bugs or technical challenges.

-

Extraction of Libraries to Improve DX: To address these challenges, commonly used patterns and solutions are often encapsulated into libraries or frameworks. These tools aim to standardize best practices, reduce repetitive code, and simplify complex tasks. By using these libraries, developers can more easily implement the new patterns, leading to an improvement in DX. This stage represents a period of relative stability and efficiency in development.

-

Application Growth Leading to Decline in UX: Over time, as more features are added, the application tends to grow in size and complexity. This increase can lead to performance issues such as slower load times or less responsive interfaces, negatively impacting UX. The initial benefits of the new pattern might be overshadowed by the bloated or complex nature of the larger application.

-

Local Optimizations Impacting DX: To counteract the UX degradation, developers often resort to local optimizations. These optimizations may involve fine-tuning code, implementing hacks, or making small-scale changes to improve performance or user experience. While these optimizations might enhance UX in the short term, they can complicate the codebase, making it more difficult to understand, maintain, and develop further. This leads to a deterioration in DX, as the complexity of the code increases and the ease of development decreases.

Conclusion

In this article, we've looked at how different technologies have grown and changed over time. We've also learned how to check and understand User Experience (UX) and Developer Experience (DX). Now, we're ready to go deeper. In my next article, we'll take a close look at each pattern. We'll see what they are used for, talk about their advantages and disadvantages, and look at the technologies that make them work. My next piece will give you a detailed and clear understanding of each strategy. So, keep an eye out for my more detailed exploration in the next article.